Eastern Cougar “Extinction” — Some Key Points

The eastern cougar is not extinct, it never existed–here is a mountain lion from the west, which genetics confirm is as much an eastern cougar as those cats that historically roamed New England.

I’ve received a lot of worried messages and comments on social media about the recent U.S. Fish and Wildlife declaration that the “eastern cougar” (or mountain lion, Puma concolor couguar) is extinct, and was therefore being removed from federal endangered species protections. I think the wording of the federal ruling unintentionally—but unfortunately—influenced how the media covered the change in conservation status.

Here is the complete federal ruling, but here I provide what I believe are the five key take-home messages for those of us invested in mountain lion conservation. This is just one man’s opinion, of course.

- There never was an “eastern puma/cougar.”

This is one point I believe should have been included in the summary at the start of the federal ruling. Yes, the fact that there is not a breeding population of “eastern cougars” in the northeast of the United States or eastern-most Canada is reason for the declaration. But, much more importantly, the newest science has revealed that there never was an “eastern cougar” subspecies to begin with.

Phylogeny is the science that proposes how animals are related by their evolutionary history. Think of phylogentic trees, something most people can remember from school, and the “tree of life” showing how animals evolved and are related to each other. Today, phylogenetics is the more appropriate term, because our study of phylogeny is almost entirely dependent upon genetic tools.

In the old days, phylogeny was proposed based upon morphology (the shape, color, and external characteristics of an animal and its skeleton). Based upon subtle differences in coat color and skeletal measurements, historic scientists believed there were many subspecies of mountain lions in North America, including the eastern cougar. Genetic tools, however, have provided a very different picture.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently recognizes six subspecies of mountain lions, of which only one—Puma concolor cougar—inhabits North America. This means that current genetic research supports the belief that all the mountain lions in North America are of a single subspecies. In other words, the eastern cougar was never a separate subspecies, and mountain lions that historically inhabited the northeast of North America were the same subspecies as the mountain lions in Idaho—which are still very much alive. Thus, the eastern cougar is not extinct—it never existed.

It is more correct to say that the North American subspecies of mountain lions is locally extinct in the northeast, because there is not a breeding population in this region.

- Recent and future mountain lions in the northeast are not eastern mountain lions.

Any recent news of mountain lion sightings in the northeast, and any future confirmations of mountain lions in the northeast, do not justify the existence of the “eastern cougar” as a separate subspecies. These are migrants from the west, not local mountain lions that survived undetected for the last 70 years. Even if there was evidence that some of these new migrants were breeding, that is still not evidence of eastern mountain lions. These are the North American subspecies of mountain lions returning to where they were extirpated some 70 years ago when wide-scale predator control was commonplace.

Some people still argue that mountain lions have existed in hidden pockets in New England for all of these years. Importantly, this does not matter because the subspecies distinction of “eastern cougar” was incorrect. But, further, most people agree this is unlikely. New England has numerous people skilled in interpreting animal tracks and sign, and mountain lions leave considerable sign where they move and kill prey.

Consider the amazing adventure of the dispersing male mountain lion that was killed on a Connecticut highway in 2011—and subsequently became national news and was written up in the book Heart of a Lion. Documenting this lone male was akin to looking for a needle in a haystack when you consider the massive geographic range he traversed, in which he unlikely ever encountered another mountain lion east of the Mississippi (if not east of Kansas). Yet, even he was documented numerous times on motion-triggered cameras and by experienced woodsmen and women while he traveled. Paul Rezendes and I were two of the many that confirmed photos of footprints he left in the Quabbin Resevoir in central Massachusetts before he was killed. My point is that even a single cat without a territory leaves sign, and a resident breeding population leaves much more.

- Eastern migrants are unaffected.

Mountain lions that disperse eastward from the west were never protected under the Endangered Species Act. Thus, current and future eastern migrants are unaffected by the new federal ruling—and still protected following the laws of the states in which they move while they are dispersing to seek new territories to call their own.

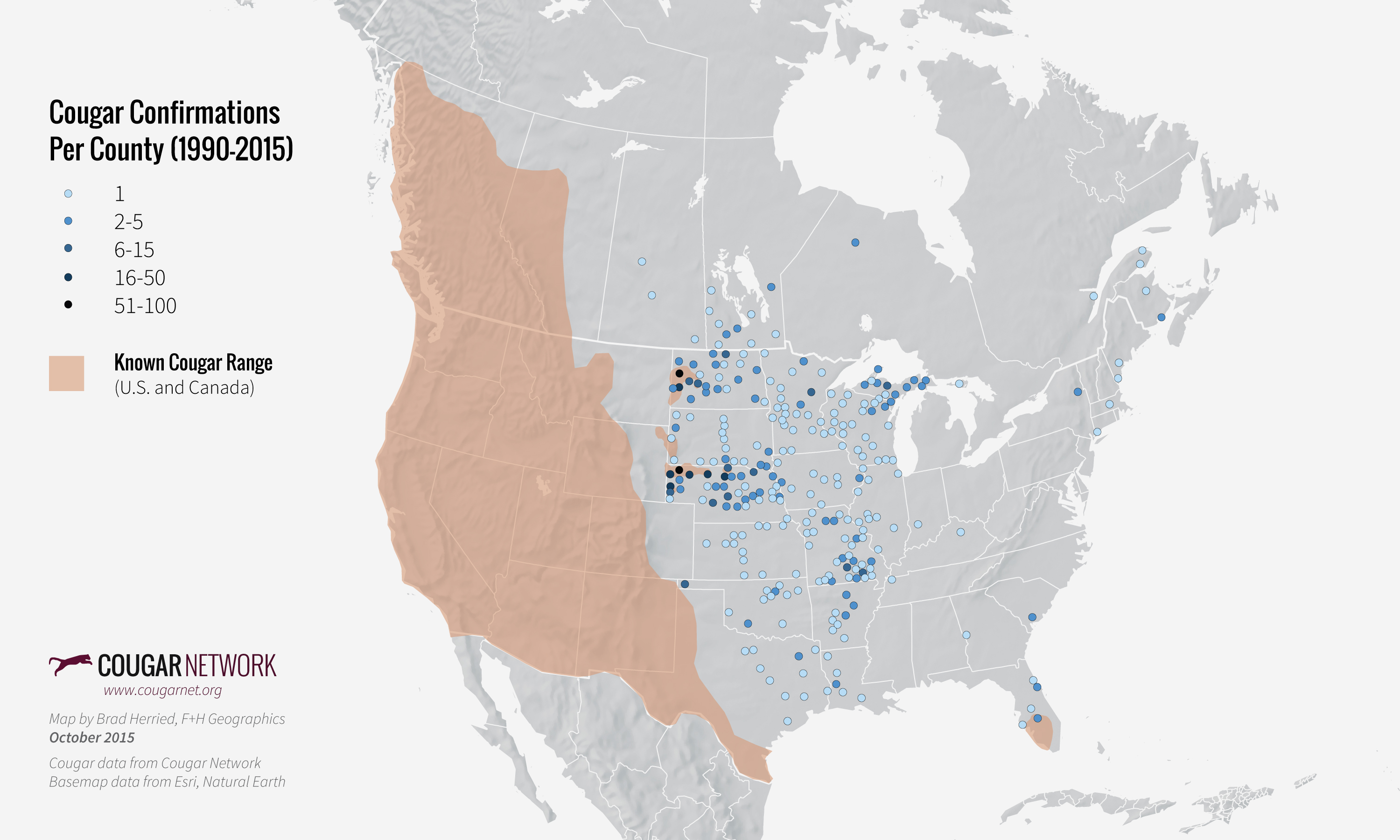

This map was made by Brad Herried for the Cougar Network, an organization leading the documenting and analyzing the eastward expansion of western mountain lions. https://www.cougarnet.org/research/

- Introducing mountain lions in the east just got easier (probably).

Re-introducing animals into previous range (as was done with wolves into Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in 1995 and 1996) is an arduous process. Re-introducing federally protected animals, which are monitored closely and have stringent rules about how they are handled and moved, is even more difficult.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and numerous conservation scientists agree that delisting the eastern cougar actually makes it easier to reintroduce this top predator in the northeast. For one reason, now that all mountain lions in North America are considered the same species, we can reintroduce the native subspecies to New England rather than replace it with a different subspecies. It will now be up to each state to decide whether that is a course they would like to pursue, however, the debates between pro-predator and anti-predator constituents are unlikely to be any easier

If you live in an eastern state that is deliberating reintroduction, or if you would like then to consider it as an option, get involved, reach out and contribute your thoughts. State Wildlife Agencies act on behalf of their public—so let them know how you feel. Certainly, there are numerous areas that could sustain mountain lions in the northeast.

- The Florida panther is unaffected (at least for now).

The Florida panther, Puma concolor coryi, is listed separately from the eastern mountain lion, and its status under the Endangered Species Act is unaffected by the recent federal ruling. The 80-100 wild Florida panthers remain protected wherever they are found, even if they disperse out of Florida into neighboring states.

The caveat, however, is that current phylogentics could be used to argue that the Florida panther subspecies, just like the eastern cougar, is not justified either, and that their protective status should be ended as well. This would be devastating for Florida panther conservation, which is currently led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This is something conservation scientists, advocates, and managers need to monitor closely as the status of Florida panther is reviewed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.