A Perfect Storm: How Multi-Jurisdictional Management Affects Mountain Lions

A subadult mountain lion, an age group our research has shown is particularly vulnerable to current management strategies. Photo by Mark Elbroch

Among the hallmarks of the American West is its mosaic of public lands, each governed by one of several state and federal agencies with different missions and objectives and, thus, varying impacts on the wildlife that call them home.

Our newest research, just published in the scientific journal Ecology and Evolution, reveals what happened to mountain lions that crossed jurisdictional boundaries and felt the effects of multiple management strategies simultaneously. We found that a perfect storm of three overlapping management actions dating back to the mid-1990s have contributed, sometimes unintentionally, to the 48-percent decline in the mountain lion population north of Jackson, Wyoming.

It all started in 1995 and 1996, when wolves absent since 1926 were re-introduced to Yellowstone National Park as part of efforts to restore natural and cultural resources to lands overseen by the National Park Service. Without a doubt, this is one of the most successful conservation stories of all time, both in terms of its cascading ecological benefits for a complex ecosystem and the social benefits it brought to our people.

In about 2000, managers turned their attention to the Jackson elk herd, the primary food source for the mountain lions we studied. A collaboration between state and federal agencies set forth objectives to reduce the herd from about 16,000 to 11,000 animals through “liberal” hunting measures. This objective, too, has been achieved in recent years.

Finally, in 2007, the Game Commission for Wyoming Game and Fish Department encouraged increased mountain lion hunting on public and private lands across the state to reduce mountain lion numbers and their associated risks (both perceived and real) to people and livestock. This objective, too, has been achieved. The results of these three different management actions have brewed unexpected outcomes, and been hard on mountain lions.

M68, a subadult male mountain lion in the background, chased off his kill by the wolf in the foreground in northwest Wyoming.

Our research focused on mountain lion mortality rates, using 14 years of monitoring data from 134 individually marked mountain lions. Wolves impact local mountain lions in multiple ways, but one of them is by killing kittens. Even while people were increasingly killing adult and juvenile mountain lions across the state to meet State objectives, wolves had begun killing mountain lion kittens after being restored to the area. Wolves were responsible for the death of at least 18% of the kittens we followed (we were not always able to determine the cause of death).

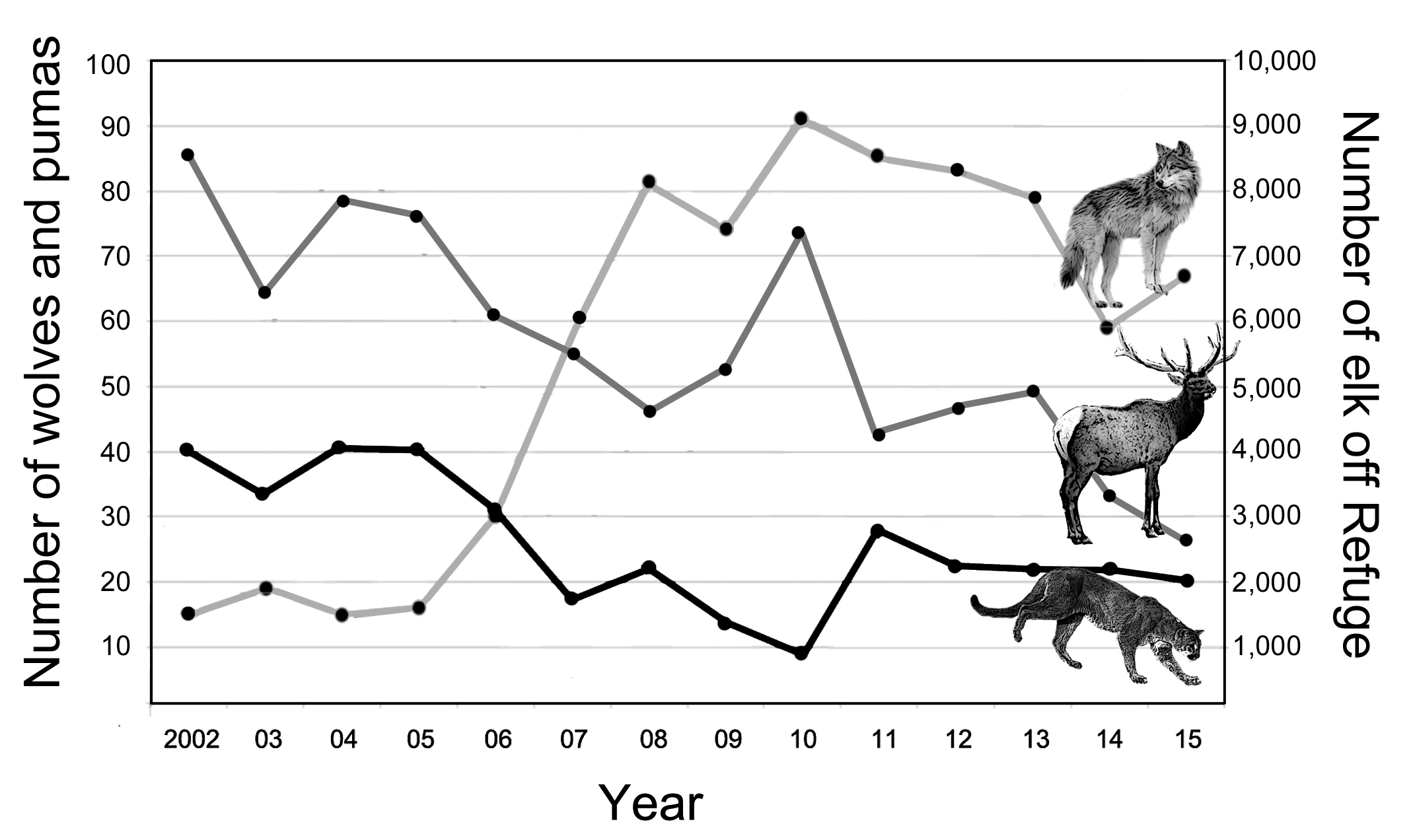

Simultaneously, wolves were influencing where elk congregate on the landscape, and how many were available for mountain lions to hunt. The distribution of elk, in fact, has become vexingly skewed, and contrary to efforts by managers to encourage a broader distribution, a greater proportion of the remaining herd winters on the National Elk Refuge each year. Local biologists attribute this change to wolves and changing weather patterns.

Elk that congregated in the open on the Refuge were still prey for wolves, but not for mountain lions that could not compete with wolves away from the protection of trees and cliffs. As elk numbers dropped in our study area, following established management objectives to reduce the herd, they also changed their distribution. In combination, this has resulted in an amazing 70-percent reduction in the number of elk that winter on native range surrounding the National Elk Refuge, where they can be hunted by and sustain local mountain lions. Juvenile mountain lion survival plummeted, and we saw mountain lions of all ages increasingly die from starvation.

70 percent reduction is huge! And the remaining 30 percent of elk—around 2,500 individuals—must now be shared with the local wolf population, which over the course of the study increased by 600 percent and now outnumber mountain lions at least 3 to 1. Suddenly, it doesn’t seem so surprising that mountain lion numbers are down—adults and kittens are being killed, and their food resources are greatly reduced.

70 percent reduction is huge! And the remaining 30 percent of elk—around 2,500 individuals—must now be shared with the local wolf population, which over the course of the study increased by 600 percent and now outnumber mountain lions at least 3 to 1. Suddenly, it doesn’t seem so surprising that mountain lion numbers are down—adults and kittens are being killed, and their food resources are greatly reduced.

We’ve just completed the next step in our research, which is to make recommendations to aid the recovery of mountain lions. Unsurprisingly, we emphasize the need to redistribute elk on the landscape, a concept easy to propose but very difficult to implement on the ground in a system with multiple predators, multiple jurisdictions, and multiple management objectives all interacting with each other in sometimes unexpected ways.

We also recommend reducing mountain lion hunting in areas where wolves are rebounding—the cascading effects of their presence are apparently too much for the cats to handle when already under pressure from human hunters. Finally, this study shows the need for managing whole ecosystems in complex areas like the West where various stakeholders hold different objectives for wildlife, sometimes complimentary, sometimes contradictory. In this case, it is the mountain lion that suffered.

Join us on Facebook.