The Olympic Cougar Project

M16, a male puma being followed as part of the new Olympic Cougar Project. Photograph by Mark Elbroch

Panthera’s Puma Program has been silent for awhile, but we’ve not been idle. We’ve been changing and growing, and we’re launching new projects in both North and South America. Here, we introduce the Olympic Cougar Project. It is a large-scale, multi-national collaborative effort, in which we’re assessing mountain lion (or cougars as they are locally called in the Pacific northwest) connectivity in western Washington State.

Previous research on the genetic diversity of mountain lions in Washington State highlighted that cats on the Olympic Peninsula west and south of Seattle may already be in trouble. They are genetically less diverse than those on the mainland, likely because the Peninsula’s mountain lions are isolated from mainland populations. Without doubt, the situation is getting worse.

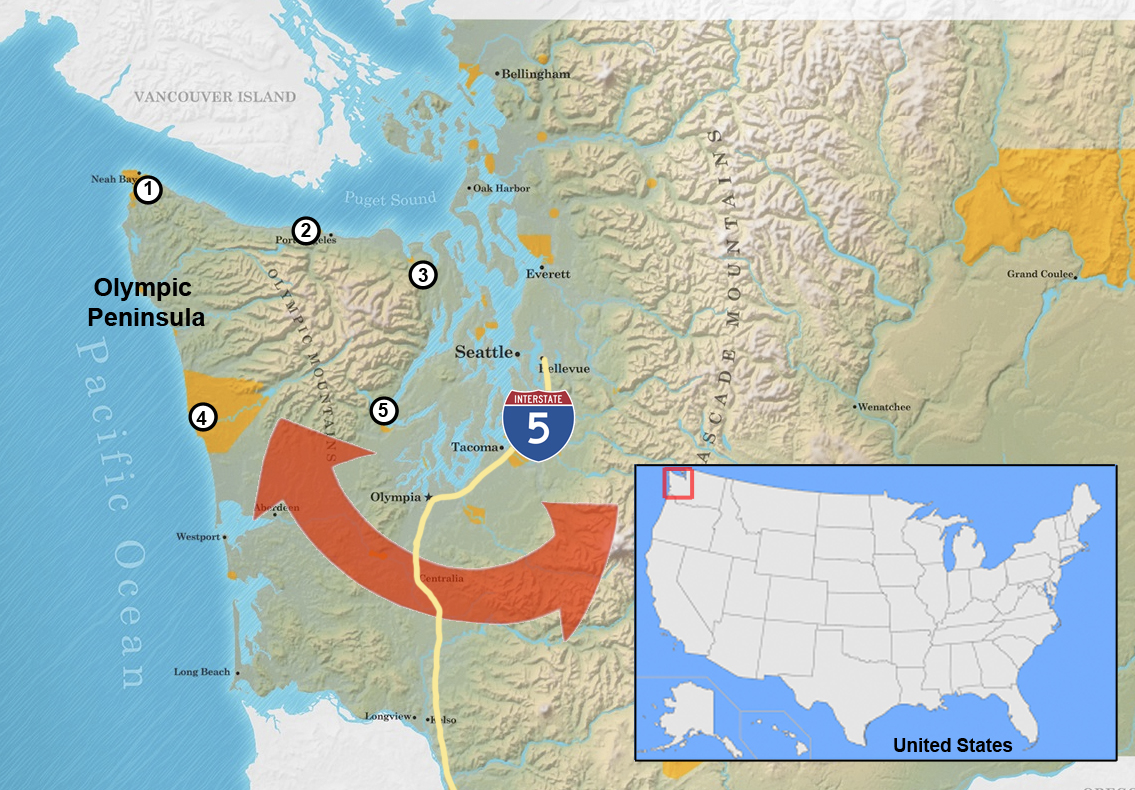

The Olympic Peninsula is fast becoming an island. The Interstate-5 (I-5) highway corridor south of Seattle is one of the fastest developing regions on the west coast, and is increasingly severing wildlife connectivity in western Washington.

Location of the Olympic Cougar Project. The red arrow denotes connectivity between the Peninsula and the mainland across the I-5 corridor. 1=Makah Tribe, 2=Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, 3=Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, 4=Quinault Tribe, 5=Skokomish Tribe

South of the peninsula lies the massive Columbia River, forming a considerable barrier for mountain lions traveling that direction. Discharging more water than any other river in the northwest, a mountain lion would need to swim about 6 miles to cross the mouth of the river. Mountain lions that wind their way eastward, closer to I-5, can shrink that crossing to a feasible swim as short as 2/3 of a mile. There are stories of mountain lions swimming across water bodies up to a mile wide, but much of the river south of the Olympic Peninsula is 2-6 miles wide.

West of the peninsula lies the Pacific Ocean, and to the north the Strait of Juan de Fuca which, at its narrowest point, offers a 15-mile swim to Vancouver Island across shipping lanes full of massive ships and hungry orcas. The bustling Puget Sound sits to the east. Navy shipyards, ferry traffic between Seattle and offshore islands, and poisonous trace metals from old industry seeping into the estuary make this area treacherous for any wildlife, pumas included.

Looking at all the options, the south and the east are still the best possibilities for pumas to immigrate and emigrate from the Peninsula. However, this means traveling through increasingly developed areas along the I-5 corridor from Tacoma, WA southward to the Oregon border. Certainly to the south, closer to Oregon, that path is much less developed and much easier, but with time the highway will widen and infrastructure and communities will grow to create a wider developed corridor, and a noose for wildlife like mountain lions, that require large connected landscapes to maintain their health over time.

F6, an adult female mountain lion (or cougar) being followed by our new Olympic Cougar project. Photograph by Mark Elbroch

F6, an adult female mountain lion (or cougar) being followed by our new Olympic Cougar project. Photograph by Mark Elbroch

Ultimately, our goal is to map mountain lion connectivity, identify bottlenecks and blockages in wildlife corridors, and work with state developers to ensure I-5 is modified to aid wildlife on the Olympic Peninsula for generations to come. Within this umbrella, we’re also studying mountain lion dispersal, assessing competition between mountain lions and bobcats, and working with an incredible array of talented scientists to analyze movement and genetic data collected from mountain lions throughout western Washington.

Our core team is composed of people working for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (LEKT), and Panthera scientists. LEKT received funds from the Administration for Native Americans to study mountain lions and predation as part of building their Seventh Generation Wildlife Management Plan, to guide the Tribe in the sustainable use of natural resources. Kim Sager-Fradkin, Wildlife Program Manager, leads the LEKT team, and I lead the Panthera team. Cameron Macias is the first LEKT tribal member to attend graduate school to study natural resource management, and is analyzing mountain lion and bobcat genetic samples collected in our study, with support from a Panthera Kaplan Graduate Grant. Together, LEKT and Panthera are forging alliances with additional tribal partners and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Department to share existing data sets and strategically gather additional data to fill knowledge gaps on the Peninsula’s wild cats.

An intimate video of M16 as he investigates his first encounter with one of our motion-triggered video cameras.

With the Olympic Cougar Project, we’re attempting something bold, something big, and something swift to protect key routes that will maintain and increase connectivity among pumas in western Washington. In the face of industrial development, urban sprawl and natural hazards, it’s a colossal undertaking, but the results will be rewarding beyond belief. If we succeed, and we will, our work may save untold thousands of cats and other animals long into the future. Join us to support the effort. And stay tuned, there is so much more to come from the Olympic Cougar Project.

We’re also on Facebook!