Eastern Cougar “Extinction” — Some Key Points

The eastern cougar is not extinct, it never existed–here is a mountain lion from the west, which genetics confirm is as much an eastern cougar as those cats that historically roamed New England.

I’ve received a lot of worried messages and comments on social media about the recent U.S. Fish and Wildlife declaration that the “eastern cougar” (or mountain lion, Puma concolor couguar) is extinct, and was therefore being removed from federal endangered species protections. I think the wording of the federal ruling unintentionally—but unfortunately—influenced how the media covered the change in conservation status.

Here is the complete federal ruling, but here I provide what I believe are the five key take-home messages for those of us invested in mountain lion conservation. This is just one man’s opinion, of course.

- There never was an “eastern puma/cougar.”

This is one point I believe should have been included in the summary at the start of the federal ruling. Yes, the fact that there is not a breeding population of “eastern cougars” in the northeast of the United States or eastern-most Canada is reason for the declaration. But, much more importantly, the newest science has revealed that there never was an “eastern cougar” subspecies to begin with.

Phylogeny is the science that proposes how animals are related by their evolutionary history. Think of phylogentic trees, something most people can remember from school, and the “tree of life” showing how animals evolved and are related to each other. Today, phylogenetics is the more appropriate term, because our study of phylogeny is almost entirely dependent upon genetic tools.

In the old days, phylogeny was proposed based upon morphology (the shape, color, and external characteristics of an animal and its skeleton). Based upon subtle differences in coat color and skeletal measurements, historic scientists believed there were many subspecies of mountain lions in North America, including the eastern cougar. Genetic tools, however, have provided a very different picture.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently recognizes six subspecies of mountain lions, of which only one—Puma concolor cougar—inhabits North America. This means that current genetic research supports the belief that all the mountain lions in North America are of a single subspecies. In other words, the eastern cougar was never a separate subspecies, and mountain lions that historically inhabited the northeast of North America were the same subspecies as the mountain lions in Idaho—which are still very much alive. Thus, the eastern cougar is not extinct—it never existed.

It is more correct to say that the North American subspecies of mountain lions is locally extinct in the northeast, because there is not a breeding population in this region.

- Recent and future mountain lions in the northeast are not eastern mountain lions.

Any recent news of mountain lion sightings in the northeast, and any future confirmations of mountain lions in the northeast, do not justify the existence of the “eastern cougar” as a separate subspecies. These are migrants from the west, not local mountain lions that survived undetected for the last 70 years. Even if there was evidence that some of these new migrants were breeding, that is still not evidence of eastern mountain lions. These are the North American subspecies of mountain lions returning to where they were extirpated some 70 years ago when wide-scale predator control was commonplace.

Some people still argue that mountain lions have existed in hidden pockets in New England for all of these years. Importantly, this does not matter because the subspecies distinction of “eastern cougar” was incorrect. But, further, most people agree this is unlikely. New England has numerous people skilled in interpreting animal tracks and sign, and mountain lions leave considerable sign where they move and kill prey.

Consider the amazing adventure of the dispersing male mountain lion that was killed on a Connecticut highway in 2011—and subsequently became national news and was written up in the book Heart of a Lion. Documenting this lone male was akin to looking for a needle in a haystack when you consider the massive geographic range he traversed, in which he unlikely ever encountered another mountain lion east of the Mississippi (if not east of Kansas). Yet, even he was documented numerous times on motion-triggered cameras and by experienced woodsmen and women while he traveled. Paul Rezendes and I were two of the many that confirmed photos of footprints he left in the Quabbin Resevoir in central Massachusetts before he was killed. My point is that even a single cat without a territory leaves sign, and a resident breeding population leaves much more.

- Eastern migrants are unaffected.

Mountain lions that disperse eastward from the west were never protected under the Endangered Species Act. Thus, current and future eastern migrants are unaffected by the new federal ruling—and still protected following the laws of the states in which they move while they are dispersing to seek new territories to call their own.

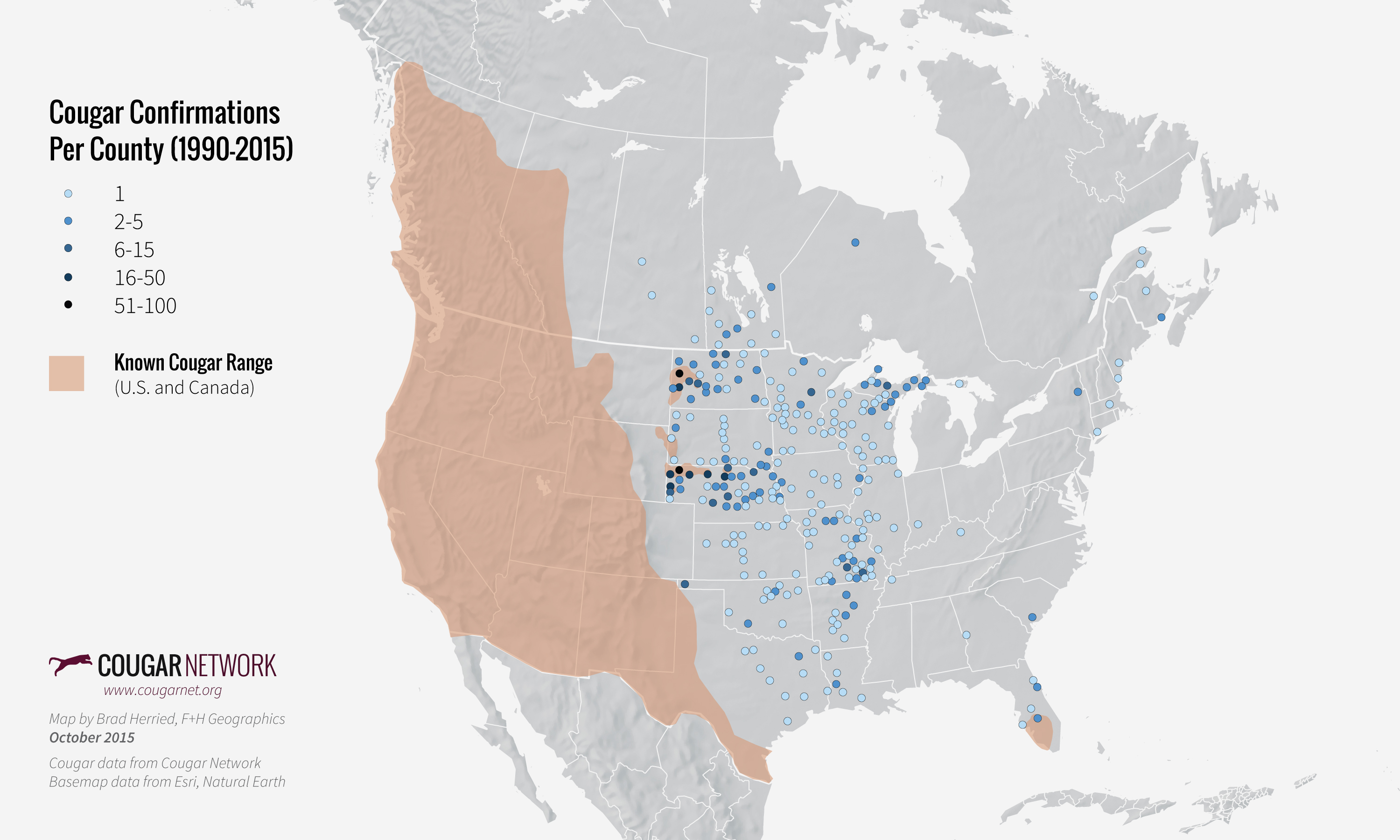

This map was made by Brad Herried for the Cougar Network, an organization leading the documenting and analyzing the eastward expansion of western mountain lions. https://www.cougarnet.org/research/

- Introducing mountain lions in the east just got easier (probably).

Re-introducing animals into previous range (as was done with wolves into Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in 1995 and 1996) is an arduous process. Re-introducing federally protected animals, which are monitored closely and have stringent rules about how they are handled and moved, is even more difficult.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and numerous conservation scientists agree that delisting the eastern cougar actually makes it easier to reintroduce this top predator in the northeast. For one reason, now that all mountain lions in North America are considered the same species, we can reintroduce the native subspecies to New England rather than replace it with a different subspecies. It will now be up to each state to decide whether that is a course they would like to pursue, however, the debates between pro-predator and anti-predator constituents are unlikely to be any easier

If you live in an eastern state that is deliberating reintroduction, or if you would like then to consider it as an option, get involved, reach out and contribute your thoughts. State Wildlife Agencies act on behalf of their public—so let them know how you feel. Certainly, there are numerous areas that could sustain mountain lions in the northeast.

- The Florida panther is unaffected (at least for now).

The Florida panther, Puma concolor coryi, is listed separately from the eastern mountain lion, and its status under the Endangered Species Act is unaffected by the recent federal ruling. The 80-100 wild Florida panthers remain protected wherever they are found, even if they disperse out of Florida into neighboring states.

The caveat, however, is that current phylogentics could be used to argue that the Florida panther subspecies, just like the eastern cougar, is not justified either, and that their protective status should be ended as well. This would be devastating for Florida panther conservation, which is currently led by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This is something conservation scientists, advocates, and managers need to monitor closely as the status of Florida panther is reviewed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

7 thoughts on “Eastern Cougar “Extinction” — Some Key Points”

Comments are closed.

Nicely summarized.

Great points, Mark. Thank you!

Great article, and I have a couple questions:

1. Does it really matter that the FL panther is not a distinct subspecies? I thought the ESA covered endangered “populations”, as well as endangered subspecies and species. The FL panther is certainly a distinct population.

2. You say that migrants from the west to the eastern US are not protected. Why aren’t they? Once arriving in the east, aren’t cougars then present, and therefore eligible for listing and protection? What if migrants establish a breeding population? Wouldn’t they then be eligible for listing and protection? If so, then not protecting the single migrant seems to defeat the intention of the ESA.

Great questions!

Regarding your question 1: Many speculate that the USFWS may switch the listing of the Florida panther to one based upon what is called a “distinct population segment (DPS).” And this is what you are referring to when you rightly point out that the ESA can indeed protect a “population” rather than a subspecies. This I think would be the best outcome for the Florida panther… but I do not know how the review team will weigh the requirements to assign DPS–the first requirement is that a population is “discrete.” Traditionally, this was clearer–the Florida panthers are clearly separate from the remainder of mountain lion populations, and anyone could see that they are discrete. But increasingly, researchers assess genetic distance instead (or sometimes, in addition to physical distance)–if indeed the genetics of Florida panthers are the same as other North American mountain lions, this measure will no longer support DPS. So, physical distance will be the key to DPS listing, which I personally believe is warranted. That brings us to the second criteria for DPS designation, which is “significance” — the Florida panther population is significant as it is the only wild population of mountain lions on the eastern seaboard. It is unique. This is my opinion, of course, which highlights the fact that each of these criteria needs to be interpreted, and how different reviewers might come to different conclusions. We must await summer 2019, when the review of the Florida panther is complete and results will be made public.

Question 2. Let’s assume that indeed migrants arrive and establish a breeding population in New Hampshire. Likely, if this happens, they will have established breeding populations further west before hand–Illinois then New York then Vermont and then finally New Hampshire. In this case, the distance the NH population is from the nearest breeding population is unlikely to support DPS listing. As discussed above, genetic distance will not support DPS listing either. And last, some funny wording in the ESA regarding DPS status–is that it “must be used sparingly.” Given the current trend of the current administration with regards to wildlife issues, this might be a tough sell for awhile. But hopefully this helps you see some of the hurdles–a breeding cat population would need to spring up right now in New Hampshire and be completely disconnected from other mountain lion populations to be even considered for DPS status…and the eastward expansion of mountain lions is slowly happening (at the speed of female dispersal, not male) and thus its unlikely a breeding population would spring up so far ahead of natural recolonization as it is already occurring. And to answer a possible question from some one else, should New Hampshire or another eastern state choose to reintroduce mountain lions, they will almost certainly do so with the provision that DPS status cannot be implemented, which would hinder the state from “flexible” management of the reintroduced animals.

Hope that helps! Thanks for keen questions.

Thanks for the clarifications! So it seems that realistically the only way cougars recolonizing the east on their own might get protection is by triggering state ESA laws, where such laws exist.

Even though reintroduction is now “easier”, I find it inconceivable that any eastern state would actually chose to reintroduce them. People in MA freaked out over a proposal to reintroduce the timber rattlesnake to an island in the Quabbin Res. It’s hard to imagine a state deciding to reintroduce a big scary cat that has been known to attack humans.

Interesting info about the possible need for genetic discreteness on the FL panther. It will be interesting to see how that plays out. It doesn’t seem that FL will ever be able to meet the requirements for delisting through recovery, which I think requires establishment of at least 2 additional breeding populations outside south FL(?). Development has gone on unchecked, and increasing numbers of panthers become road kill.

Again, thanks for the additional info. I really admire your work and wish you continued success.

How can I subscribe to this blog?

I’m not sure! Sorry–I’ll try to figure it out.